Project Quality: Aligning Technology and the Human Element

If you read about any industry these days, you could be forgiven for thinking that increased use of technology will fix pretty much anything.

This suspect thinking could be applied to the design and construction industry, too, although research firm McKinsey says the construction industry has invested too little in digital technologies, its report notes.

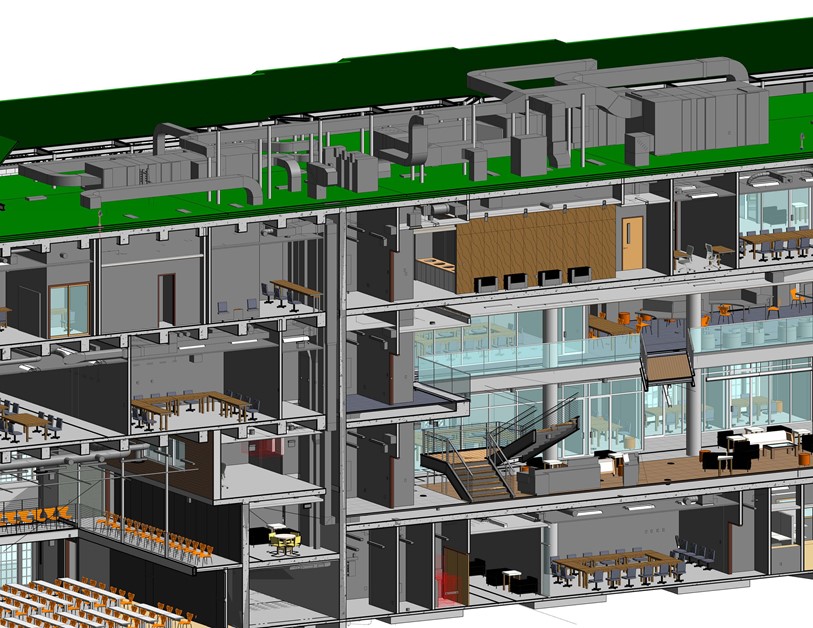

As architects in the higher education sector, we see firms, including our own, adopting sophisticated project management platforms such as Newforma, an array of product, materials and detailing resources such as Architizer and AEC Design Transparency, and Building Information Modeling (in our case, Autodesk REVIT).

With these tools, we more easily create working models that consider all aspects of construction, including building details, anticipated conflicts and even compatibility-coordination between trades. As such, we move into construction with a strong sense that what has been designed and documented can readily be constructed—on time and on budget.

And then ... stuff happens. When projects run into cost overruns and delays, it’s not usually because too little technology was used, but because too little quality control guided that technology.

In every industry, technology is just a tool to do things in a different and, hopefully, more efficient manner. Technology, in and of itself, is never the sole answer. To consistently improve quality and realize high expectations, there are five overarching principles that are critical.

Own the work

Modeling tools such as REVIT provide default settings for basic building components and assemblies in a manner that, without scrutiny, suggests a deceiving level of resolution. Without careful tracking and coordination, what is drawn may not fully support the design intent or integrate well with other assembles. Too often, staff may be in command of the BIM program, but are inexperienced and producing models they don’t understand. There is also a perception that we rely too much on BIM to do our thinking for us. This can lead to uncoordinated documents with insufficient detail, inadequate bids, unreliable planning and cumbersome and costly changes in the field.

"Own the work" means the design firm owns it from the get go, and makes sure that what’s produced reflects the design intent and what will be built. "The Principal needs to be on top of things, accountable from start to finish," says Bert Jones, Associate Vice Chancellor, Virginia Community College system.

Demand completeness and clarity

Accelerated schedules and compressed planning and programming, based on assumptions and conjecture rather than investigation and analysis, is often the new normal. Technology can speed production and assembly tasks, but there’s no substitute for thinking and coordination tailored to the project. Default settings and placeholders can be automated. Real solutions require our attention. Demand an accurate program, meticulously defined scope, vetted detailing, and budget and schedule clarity.

Check processes, tools, techniques

Attaining quality on a consistent basis requires the best processes, tools, techniques, knowledge, experience, and a culture of collaboration and mentoring. Up-down mentoring is critical. Younger staff can tutor senior architects in BIM on technical skills. Senior staff needs to share knowledge and insights from their years of experience. When engaging a Construction Manager (CM), do so early in design to integrate their expertise, too. An architect's input in the CM selection can better ensure compatibility. Peer reviews at project milestones by a third party - an individual, in-house studio, or external firm - is recommended by the AIA Trust. Public agencies, like the Virginia department of General Services, offer quality and standards guidelines with check-lists such as those included in the Construction and Professional Services Manual (CPSM).

Foster collaboration

Doing so among the whole team - consultants, contractor and owner - while providing incentives for positive, non-adversarial outcomes, can enhance quality. In the state of North Carolina, collaboration is considered as part of an evaluation of the CM and Designer at project end. Negative evaluations diminish the prospect of future opportunities. The need for team collaboration is only increasing with ever more aggressive schedules, sustainable design expectations, and owners looking for greater value at reduced cost.

Coordinate communication - Client Consultant Collaboration

Here, we attack what is often the weakest link in the process, communication - among the principals, project managers, job captains, and staff and consultants that make up project teams and the project owner, too. Owners are responsible for providing clear and timely information, maintaining decision and approval protocol and, perhaps most importantly, thorough document examination and input through the entire project process.

"The definition of a great owner -- one that can have a positive impact on a project -- is one who maintains a disciplined decision-making process and rewards team collaboration," writes Barbara White-Bryson in The Owner’s Dilemma.

Bottomline: It takes everyone in every facet of the process to be attentive, to establish and follow agreed upon protocols, and to resolve to communicate. Technology should never be blindly trusted, and the human element needs to be tenaciously tracked.

Written with contributions from Robert V. Reis, AIA, LEED AP and Bill Hopkins, AIA