P4: The Role of Planning in Successful Public Private Partnerships (P3s)

“Adding that Critical P to Your Process”

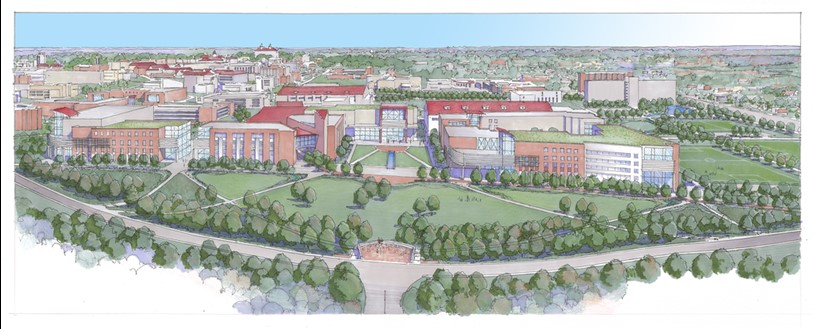

After three years of discussion, the University of Kansas recently approved a $350 million public-private partnership, or P3, to redevelop its campus and build a new science building, residence hall, dining facility, apartment complex and even parking and utility facilities.

The P3—reportedly the first of its size in Kansas at a university—is just one of the latest in a long list of public-private partnerships sweeping into higher education institutions nationwide.

Yet for every P3 that gets off the ground, we suspect many more never come to fruition. That’s because such deals are complex and involve a tricky set of tradeoffs and benefits. That’s why we think P3s really should be called P4s, with the fourth “P” for “Planning.”

In general, public private partnerships occur when an institution leases university-owned land to a developer to build and manage a property. In the past ten or so years, most of the P3 projects on colleges and universities have been residence halls, which produce a clear revenue stream for investors. Often times, these projects were near campus edges or on outparcel properties. Now, as the KU deal illustrates, P3s are expanding into more areas of campus and more assets that were once purely governed for and by public entities are becoming enmeshed with private enterprises. At a recent Academic Impressions conference on campus planning, 75 percent of attendees indicated the most sincere exploration of P3s on their campuses existed beyond the scope of student housing.

Schools in a Pinch

Partnership means the deal has to work for both sides. That means private enterprises who fund, build and perhaps manage new campus facilities also need to make them financially profitable. In exchange, financially strapped institutions get buildings built, often more quickly than if they went it alone. Construction costs can be lower, too, and institutions avoid, at least in the short term, taking on more or as much debt.

As architects and planners to America’s universities and colleges, we’re acutely aware of the financial pinch facing many institutions. Despite recent increases, state funding for higher education still remains below 2008 levels while enrollment in public higher education is up almost 9 percent from the start of the recession, the Center on Budget Policy Priorities recently reported. Meanwhile, our nation’s campuses are filled with outdated and aging facilities. Given all this, it’s not surprising that higher education institutions have turned to P3s.

Planning Mitigates Pitfalls

Yet we also see risks with the P3 trend that a P4 mindset can help mitigate.

More than once, we’ve seen a campus master plan—the roadmap for an institution’s development—get leapfrogged in the process of putting a P3 into place. This often results in a compromise of the design integrity of a campus ecosystem and may wind up costing more than institutions think.

Campuses are, after all, no less than small, and sometimes not so small, cities. They have hearts, histories and architectural and cultural bones. Just one change to a campus, say a new student housing complex, has spillover impacts to the entire campus in terms of vehicular, pedestrian and bicycle traffic, energy usage, even drainage patterns. These are the things accounted for in a master plan. In haste to get projects done—and done profitably—the private part of a P3 has less of a sustainable interest in the entire campus ecosystem than will the public part of the partnership – its simply not part of the business deal.

Meanwhile, in their desire to meet a pressing need, an institution may be enticed to use a parcel of land intended for something else. No piece of land should ever be given over without a long-range assessment of what will be fully lost for years, and even generations.

Several years ago, Boise State University called off a private equity deal with a developer for a large residence hall partly because of worries about signing an 85-year deal, a New York Times article noted. “Who knows what the university may need to use its land for in that kind of a time frame?” the university’s architect was quoted as saying.

Weighing the P3 as part of a master plan is critical. Asking questions—and the right ones—is also critical. After all, institutions often give up control of valuable real estate when they engage with a P3.

The student housing and dining master plan we developed with Arizona State was essential to the university in understanding what they needed and helped them determine that P3 was the right approach. Hanbury designed the Verde Dining Pavilion, seen here, which was one of the first buildings that came out of the plan.

So, what are some simple best practices to position an institution for a successful P3?:

- Invest time in pre-planning: Review the campus master plan to ensure aspects affecting P3 sites are properly updated. Consider a mini-master plan update prior to proceeding with the P3 RFP.

- Clearly define goals for the project and campus in precise detail for the RFP. Include prescriptive minimum requirements, design guidelines, and also desired added value goals. Define goals and requirements for the campus areas adjacent to sites as well as the P3 sites proper. The more detail included in pre-design efforts, the better.

- Explore the financial model of the non-P3 approach as a baseline for comparison. This provides valuable insight when considering P3 options and proposals.

- Have a clear understanding of your state’s policies, process, and construction standards requirements for P3 procurements.

- Consider including your master plan consultant as a resource to the university committee in evaluating P3 proposals.

- In evaluating options, focus on long-term objectives for the institution, not just the project or the site.

Doing the Due Diligence

We don’t expect P3s to go away nor do we think they should. Done well they are another viable alternative not only for schools but, as we’ve seen, for roads and other infrastructure. They also have a long history, writes Frank Manzo, the policy director of the Illinois Economic Policy Institute. In 1742, Manzo writes, the Pennsylvania House of Representatives turned to the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, established by Benjamin Franklin, to finance the founding of the University of Pennsylvania.

We do, however, believe that it is imperative to view a P3 as a holistic and interrelated subsystem of any institution—and not as a single entity or just an opportunity to reduce cost. This can be achieved through Planning, the fourth “P,” as part of the process.