Designing for Student Wellness

A few years ago, my daughter called my wife and I from college. It was midnight. Our daughter was so stressed she said she couldn’t breathe.

She survived that awful experience and is now happily employed with her higher education degree in the bag. Ever since that night, though, I’ve been more aware of what can be done to help reduce student stress and improve student health.

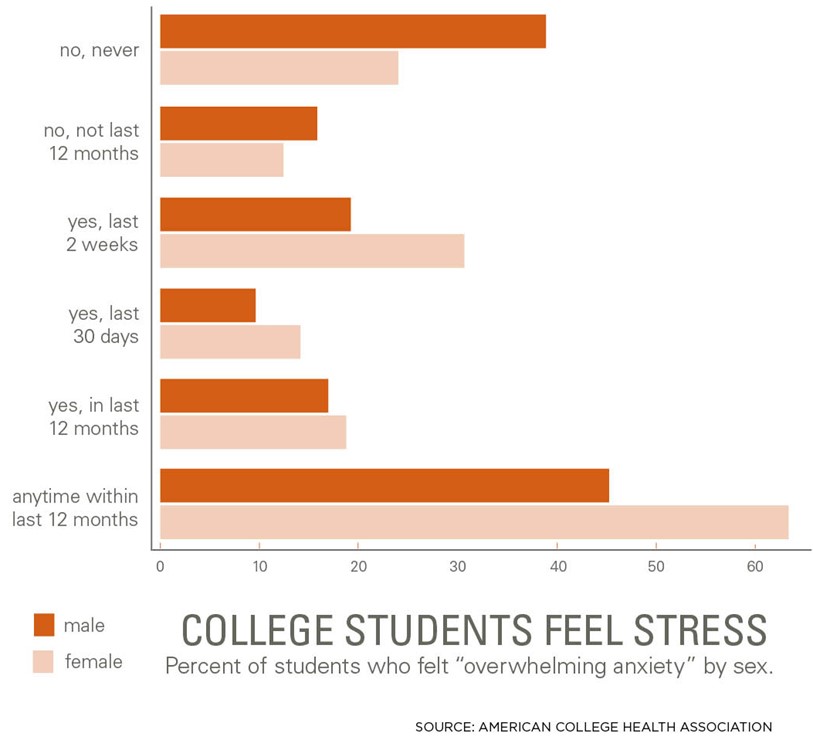

Survey results certainly indicate that more could be done. The American College Health Association’s 2015 fall survey of almost 20,000 students revealed that:

- Almost 60 percent of college students reported feeling “overwhelming anxiety” in the prior 12 months and more than 35 percent said they felt so depressed it was difficult to function.

- More than 17 percent of the students had been diagnosed or treated by a professional for anxiety, 14.5 percent for depression and 8.7 percent for panic attacks in the prior year.

The health issues were also hurting student performance.

- More than 30 percent of the students said stress had led to lower grades or dropped courses; 24 percent said anxiety had the same impact and 20 percent said sleep difficulties hurt their performance.

The fact that college students are stressed is hardly new news. Nor is it unexpected. That time of life involves leaving home, friends and a structured lifestyle for a new environment. Students may lack friends on campus, struggle with having to manage their own schedules or with heightened academic pressures.

“Their whole life and and social system changes,” says Michelle Eichinger, president of Designing4Health, a consulting firm focused on aligning public health with better building design and community planning.

Higher education institutions have already taken many steps to assist students with the transition to life in college, Eichinger notes. Students have more access to tutors, academic coaches, peer mentors and counselors. More schools now provide wellness centers and healthier food choices.

There’s also a growing focus on how buildings, as well as campus design, can improve student wellness.

Like the LEED standard for “green” buildings, there’s now the WELL Building Standard® for buildings. Launched in 2014, the WELL Building Standard is the first rating system that addresses how buildings can enhance human health and wellness. Put another way: green buildings focus on reducing impact to the environment; well buildings focus on enhancing the health of the people inside them.

The WELL building standard—crafted after seven years of research—sets performance requirements in seven categories: air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, comfort and mind.

The idea is that these things can help us feel better, be more productive and less stressed, too. Lighting is a good example. Who hasn't felt something pleasant when you enter a room that’s lit just right for the time of day and occasion? That’s because our body’s circadian rhythms are involved in all kinds of metabolic processes, including sleep. Having the right color of light in the morning helps us wake up. A whiter light for work hours keeps us focused. Softer lights at night help us relax and prepare for sleep.

The WELL Building Standard looks at all kinds of things, including lighting, that transform indoor environments into spaces that nurture, sustain and promote human health and well-being. The standard is administered by the International Well Building Institute, which was created by the New York-based developer, Delos®.

Delos has probably done more than any one company to advance the notion of well buildings. Its WELL projects include condominiums in Greenwich Village, rooms in the MGM Grand resort in Las Vegas and various office buildings. Delos has even cracked the higher education market.

The Legacy at Drexel Arms, which houses students attending St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, was designed with 25 percent of its rooms considered WELL Signature Suites. Among other things, the suites were equipped with special lighting systems and advanced air and water purification systems.

So far, more than 100 million square feet of space, stemming from more than 100 projects in 12 countries, have been certified, registered or committed to achieving the WELL Building Standard, the IWBI website says. The institute is also holding workshops to inform professionals about the benefits of WELL certification, one of which I took part in last November.

Outdoor spaces matter, too

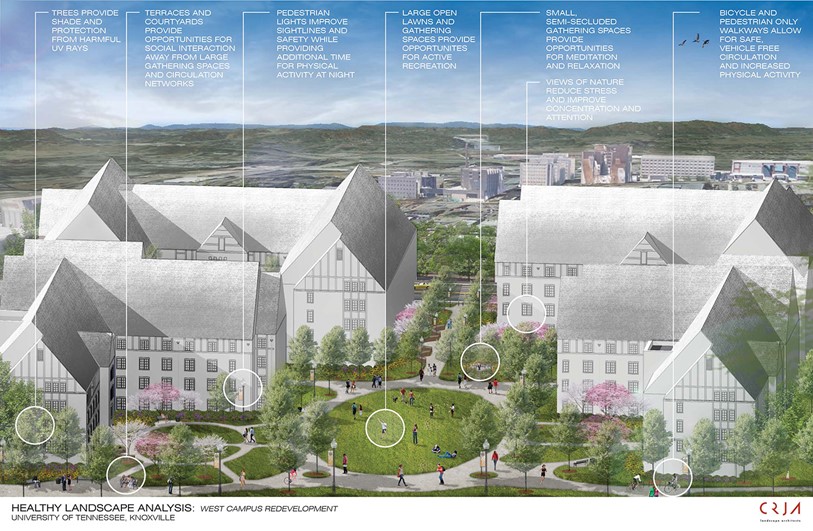

Eichinger, meanwhile, concentrates more on how outdoor areas can enhance wellness. Designing4Health, along with CRJA-IBI Group, recently created a new process that incorporates health data in design.

We are currently working with Eichinger and CRJA-IBI Group on a campus housing village project at the University of Tennessee. For that project, one focus is how outdoor gathering spaces, large and small, provide opportunities for social interaction, which helps students make connections, as well as enhanced physical activity, which helps students keep their bodies and minds more fit.

Eichinger previously worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an expert in integrating public health in land use planning and policy. She sees a “big movement” afoot in how buildings, as well as open spaces and community design, can enhance wellness.

Building on knowledge

For sure, architects and planners have long considered the human inhabitants as we design buildings. Look at almost any modern building and you’ll see more and better use of glass to enhance lighting and social connectivity. Cities and communities are more likely than ever to infuse new developments with open spaces. Even classrooms are now being designed to encourage more student engagement.

Yet any feature in a construction project will be subject to budget pressures. With well defined standards of what makes a "well" building—and new ways to measure the health impacts of certain designs—we think school administrators will have more information with which to make decisions.

My own work on designing a prototype for student housing for veterans strongly reflects how important we think design can be for wellness.

The Student Veteran House, is aimed specifically for veterans, many of whom suffer from post traumatic stress syndrome.

Through the use of focus groups, we documented that student vets are a diverse group with a wide variety of physical and psychological needs. Universal design that accommodates their needs and is dignity compliant is essential to foster independence among residents. We also saw how important it was to many of the veterans to be able to have therapy animals at school and the need for private outdoor space to accommodate them. Providing social common area and group study spaces that bring veterans together will bring back the camaraderie that they had while in the service.

We think such mindfulness can be extended to the broader campus. Delos, in an interview with the The New York Times in 2014, said it was costing about 2 percent more for a WELL project over normal construction. That much of a cost premium seems well worth it, especially if healthier buildings leads to healthier students.